Egon Schiele Austrian, 1890-1918

1920

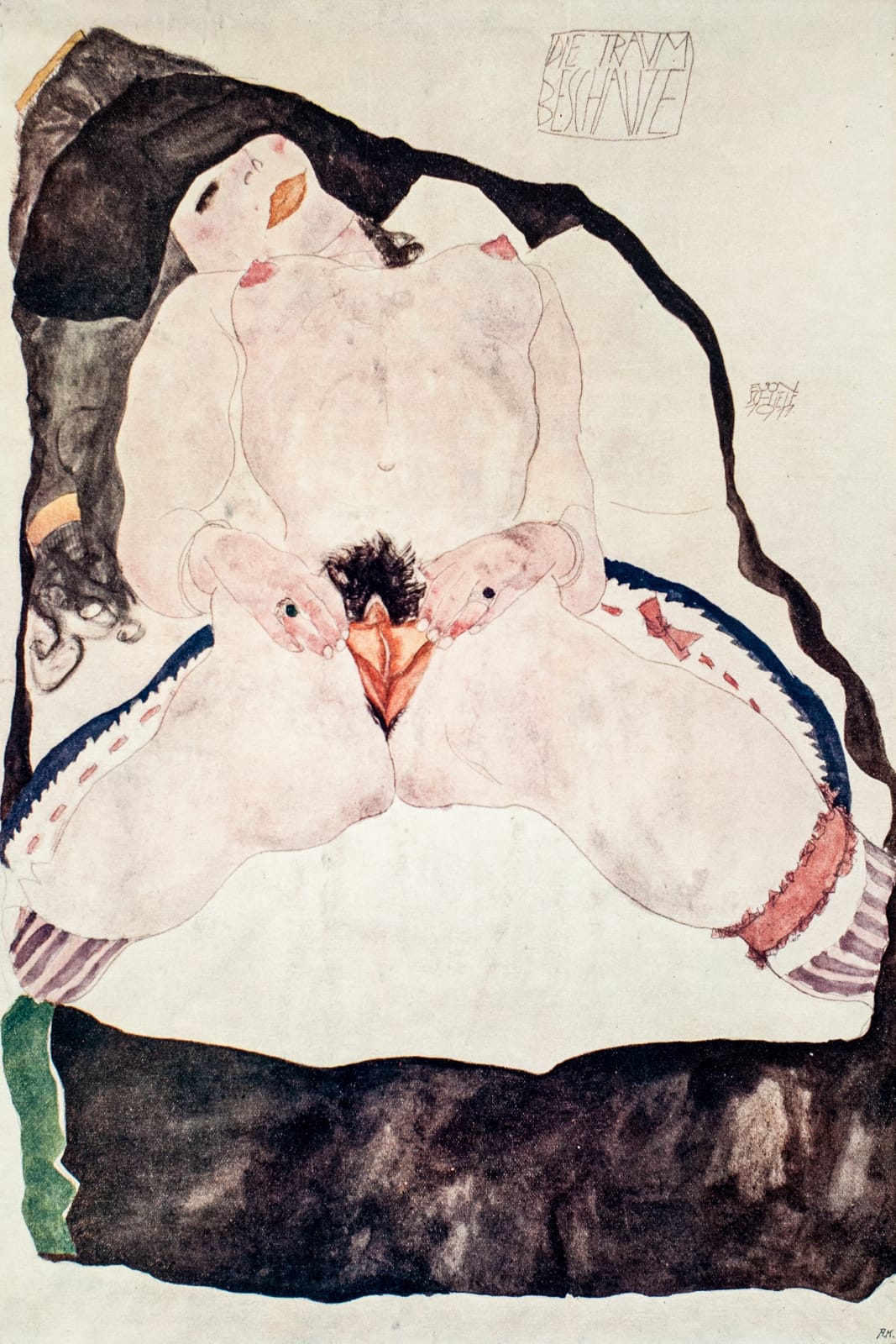

Published anonymously c. 1920, Vienna, in an edition of 100, after the original watercolor and pencil on paper, titled in the plate at the top: “DIE TRAUM/BESCHAUTE” and signed and dated in the plate middle right: “Egon/Schiele/1911”; printed in color and marked in lower right by the printer: “A.K.” who is believed to be Andreas Krampolek.

Egon Schiele’s artistic output in 1911 reveals a dramatic maturation as well as a willingness to boldly confront social taboos. In his deepening exploration into the way one sees and relates to the world, Schiele delved into literary sources such as Arthur Rimbaud and Frederic Nietzsche who pushed the boundaries of accepted thought. Within this literary context, it was Schiele’s own contemporary Vienna where the most revolutionary ideas and trends were germinating. Sigmund Freud’s seminal book, The Interpretation of Dreams, about the power of the unconscious mind, had literally taken hold of popular consciousness. By then in multiple printings, Freud found even greater mass appeal for his theses by publishing an abridged version in 1911 entitled, On Dreams. Schiele’s image and title conveys and explores Freudian dream theory which posits that civilization’s repression of an individual’s urges and impulses must result in a release somehow such as in a dream. Emboldened by Freud’s theories, Schiele continued to push his artistic inquiry into rarely treated subject matter. He invited his viewers to confront an image of a barely clad female with splayed legs whose two hands spread the labia wide to reveal her vulva and clitoris. Perhaps on first glance, the viewer might determine that this is purely a pornographic image; however, read in a Freudian context, Schiele dares to present us with the opportunity to contemplate a dream in the waking state.

As Freud asserted, dream content is often disturbing so the unconscious protects itself by coding the content as symbolic language. Here Schiele encodes his dream image by utilizing the V-shape and triangle which are symbols often used to represent the female sex. Schiele’s female figure is pyramidal; her head serves as an apex while wide legs form a base. The torso, by contrast, forms an inverted triangle with each erect nipple giving emphasis to the pyramidal theme. These triangular shapes converge upon the vagina which is yet another study of triangularity. Portrayed in this unabashed way, the vagina symbolically takes on the appearance of other species such as a flower or even a bird with its labial wings extending outwards.

There are deliberate ambiguities to Schiele’s dream construct. Only one of the female’s eyes is visible. It is closed, perhaps in repose or in a moment of orgasmic surrender, and yet his subject’s hands display her sex in a deliberate manner as one would in a conscious and rational state. Schiele demonstrates the struggle between, what Freud termed, the Id and the Ego. Viewed in such a manner, the pelvic region takes on a sort of alternate persona in avian form. The jewels adorning the rings on each hand stare out like eyes. Pubic hair crowns this Id creature like feathers over a beak. Schiele creates, not one, but two heads in this psychological portrait study: one representing the external environment and another representing the unconscious psyche. As one final trope of observation, one can trace another triangle from the one closed eye to the two jeweled eyes below which intensely confront the viewer.

As much as Schiele’s images cover bold territory, the portfolio itself has a colorful history all its own. It is one which involves censorship, destruction and trials about morality. Born out of the lofty ideas and ambitions of artists and art lovers, the portfolio represents state of the art printing in its day as well as art as interstate commerce. The erotic subject matter of Schiele’s five images included in the portfolio necessitated discretion. The portfolio printed in an edition of 100 was published anonymously. The one-time printing, as it states on the cover page, was only for subscribers. Thus, from the portfolio’s inception, there is an implication of secrecy and exclusivity. Even the printer’s contribution is cryptic. Save for the discreet initials inconsistently marked on each printed sheet, no mention is made about the printer, its whereabouts or even the year in which the portfolio was created.

Scholars now believe the printer to be Andreas Krampolek (1869-1940), a Viennese art printer specializing in the collotype process. Upon his 40th anniversary of printing in 1923, Krampolek’s work was honored with an exhibition at Vienna’s Museum of Art and Industry. That same year was also a critical one in the story of the portfolio. In September, Karl Grunwald was tried before the Regional Court for Criminal Affairs in Vienna. Accused of disseminating pornographic prints, Grunwald was charged with a violation of the law on moral grounds. The prints in question were none other than the EGON SCHIELE: FUNF ZEICHNUNGEN portfolio. Grunwald had sent this portfolio to Hans Goltz in Munich who was a former art dealer of Schiele. Grunwald offered Goltz 200 sheets, or the equivalent of 40 portfolios, for purchase. Goltz declined the offer and returned the portfolio of Schiele prints to Grunwald in Vienna. Customs authorities intercepted the package and brought charges against Grunwald. Although a jury found Grunwald to be Not Guilty of any crime, the 200 sheets from the portfolio did not fare as well. Attorney General Hofrat Formanek pushed for a separate hearing with the intention of destroyingg the 200 images. In a bold act of censorship which recalled a similar outcome in court during Schiele’s lifetime, the art prints were destroyed by the court authorities. By late-1923, only 60 portfolios remained.

Karl Grunwald and Egon Schiele had met one another several years prior during the war early in 1917. Leopold Liegler, one of Schiele’s art patrons, intervened on Schiele’s behalf in an effort to get Schiele transferred out of combat duty and back to Vienna where he could better focus on his art. Appealing to Grunwald’s sensitivity for and appreciation of the arts, Liegler suggested the Military Supply Depot in Vienna where Grunwald was stationed as an option for Schiele. Indeed, through Grunwald’s help, Schiele was transferred there on 12 January, 1917. In Grunwald, Schiele found a champion. Grunwald modeled for Schiele and befriended him. By the Spring, Schiele had hatched his ambitious plan for an artistic gathering place. Schiele’s Kunsthalle was to be a public forum where poets, painters, sculptors, architects and musicians could freely interact. Among his recruits were leading artists such as Vienna Secession founders, Gustav Klimt and Hans Hoffmann; the composer Arnold Schoenberg and art patrons Liegler and Grunwald. One of the key features Schiele enthusiastically envisioned for Kunsthalle’s commercial possibilities was to act as “its own art dealer and publisher.”

Schiele’s print portfolios were the sole fruits of this dream. Though Schiele’s Kunsthalle died on the vine, his portfolios effectively superseded the fixed art exhibition space to create a mobile concept. In 1917 bookseller Richard Lanyi published the first series of Schiele’s reproduction prints to much critical and commercial success. Following the war, Grunwald opened the gallery, Alte und Moderne Kunst in Vienna. He remained committed to Schiele, even after his untimely death in 1918, by staging an exhibition of Schiele’s work in 1921. It was only natural that Grunwald would continue Schiele’s commercial and artistic vision by publishing his own portfolio of Schiele works. FUNF ZEICHNUNGEN was Grunwald’s great contribution to Schiele scholarship. That some of the original 100 have survived is all the more significant because without this portfolio, the public today would not have a record of two key works by Schiele which, sadly, were lost during the Nazi era.