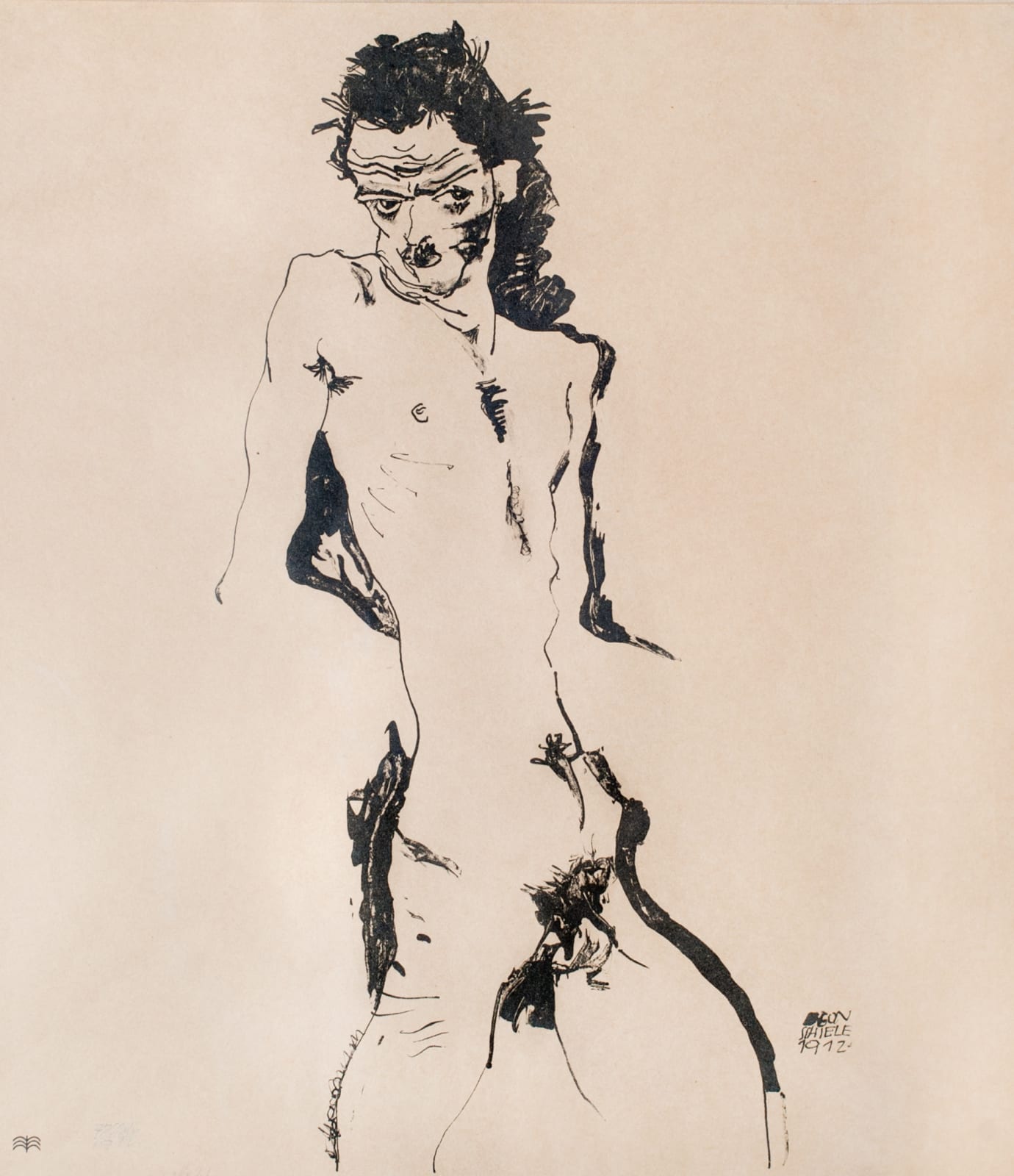

Egon Schiele Austrian, 1890-1918

1912

Further images

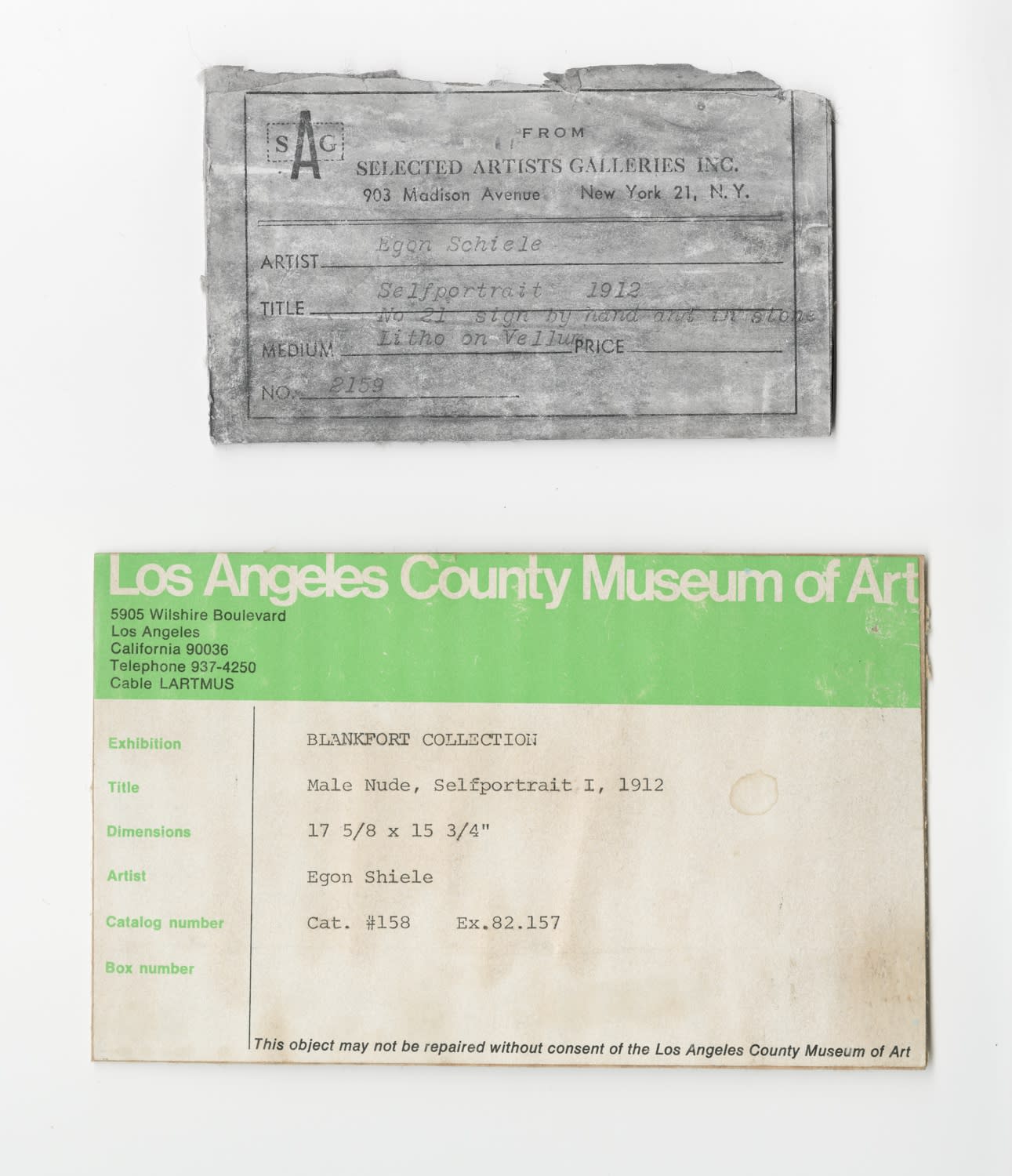

MALE NUDE (SELF-PORTRAIT) I by Egon Schiele, 1912, a brush and ink lithograph on vellum paper made for the Munich-based artists’ association, Sema 15 Originalsteinzeichnungen portfolio; Delphin-Verlag printer; the image is numbered 21 out of an edition of 215, and the sheet measures 17 3/8” x 15 3/4”; signed in the stone Egon Schiele and dated 1912 in the lower right; signed, dated and numbered by the artist in pencil in the lower left to the right of the Sema printed signet. (Kallir G. 1) Formerly in the Michael and Dorothy Blankfort collection of The Los Angeles County Art Museum, original labels verso.

Egon Schiele. a prolific draftsman, made his first print - one of only 17 graphic works created before his death in 1918 - shortly after he was invited to join the Munich artists’ association, Sema, in 1911 when he was just 21 years old. In a brutally overt, expressionist manner for which he has come to be known, Schiele’s first graphic work is the ultimate calling card announcing the artist’s arrival to the world. Naked, oddly confrontational in an open stance, yet simultaneously vulnerable and rendered physically impotent with a mutilated penis and missing limbs, Schiele conveys a powerful dissonance which sets the tone to force the viewer into considering the image as a psychological portrait. Schiele gives his figure no props such as clothing or spatial-temporal clues and thus dismisses the surface and emphasizes the substance. The most potent and concentrated areas of ink depict nothing from the observable world. Rather, the strong black outline, almost phantasmal in its thick application behind and along the hips and thighs, between the arm and torso and above the shoulder to curve around the head, finds its way to the genitalia and to the mouth in such a manner as to overtake the form, to silence and render the physical powerless. Schiele, the masterful artist, transcends the limitations of naturalism or allegory and transports the viewer to this psychogenic state of self-portraiture through the physical gesture of energetically applied ink. He uses these gestural movements, contortion and amputation of body parts as a means to access the inner state.

In Egon Schiele: A Self In Creation, Danielle Knafo astutely recognizes this subjective emphasis of Schiele’s work, particularly as it relates to his voluminous output of 250 self-portraits. “Through his confessional self-portraits, Schiele laid his life out on canvas and embarked on an analysis of his personality as deep and ruthless as Freud’s analysis of himself.”

Syphilis, which plagued Europe in the 19th and early 20th century, infiltrated the Schiele home with wide-ranging and deeply troubling effects. Schiele’s father contracted the disease, passed it on to his wife and lost four of their seven children to complications from the illness before going mad, becoming paralyzed, and finally dying when Egon was fourteen years old, forever cementing the connection of sex and death into Schiele’s psyche. These traumas of Schiele’s childhood became just as significant to his life as any experience. They assumed space in his being no differently than a vital organ, perhaps more so than certain body parts.

“…this probing into the psychology of experience, especially as it relates to childhood, to gain understanding of psychosis and human pathos firmly roots Schiele’s modern artistic expression to contemporary Vienna.” Schiele’s deeply personal analysis was a conscious one. His figural image conveys this with a directness that is aggressively confrontational. It is Schiele’s eyes which burn into the viewer with the double intensity of a voyeur and an all-seeing artist capable of capturing and reconciling the inconsistency of inner and outer states. This is no dream. Schiele’s eyes are wide open.

With this first graphic work, Schiele masterfully presents a very modern form of self-portraiture. There is certainly a young bravado about the virtuosity and spontaneity of his brush. The lithographic medium was clearly conducive to his fluid and unrestrained approach to drawing. Coupled with his intense gaze, the saturation of ink or the essence of himself, and the manipulation of his human anatomy, Schiele dares the viewer to confront him - the real Egon Schiele - and marvel at his abilities to bring full expression to the abstract inner state and give it form.