Walter Schnackenberg German, 1880-1961

1920

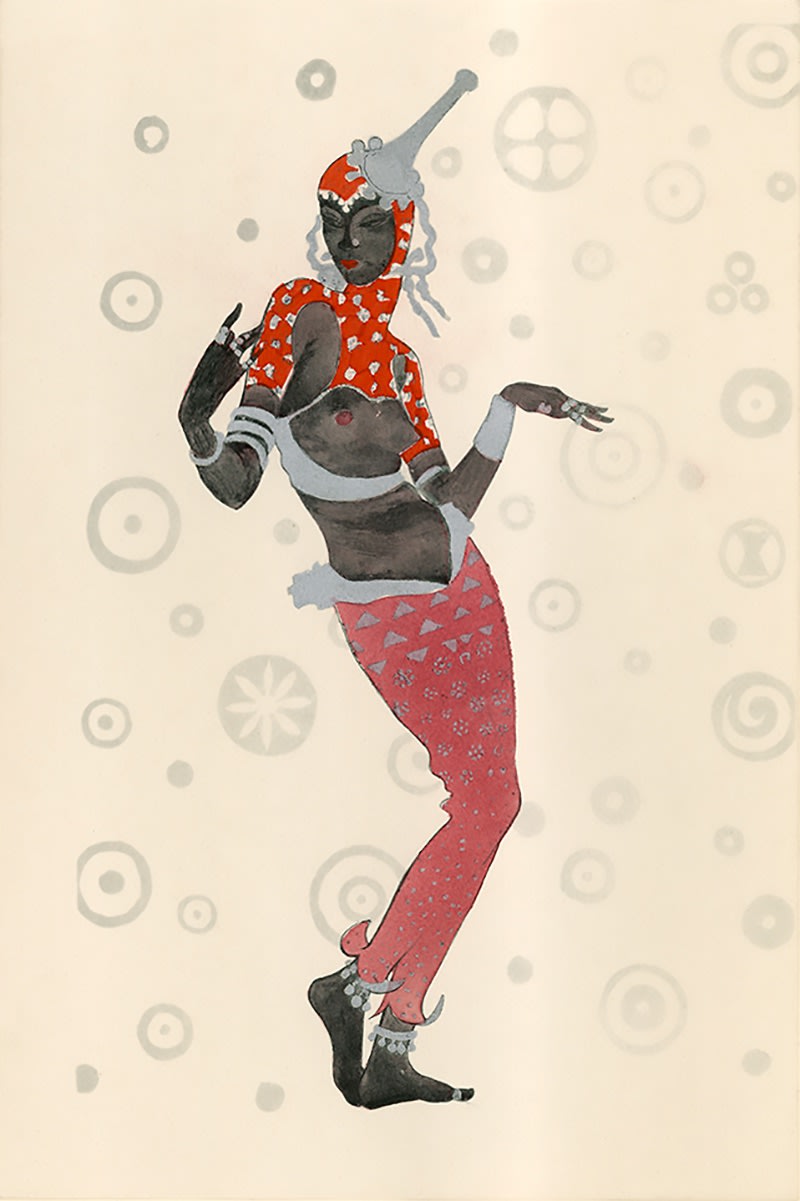

Walter Schnackenberg’s style changed several times during his long and successful career. Having studied in Munich, the artist traveled often to Paris where he fell under the spell of the Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s colorful and sensuous posters depicting theatrical and decadent subjects. Schnackenberg became a regular contributor of similar compositions to the German magazines Jugend and Simplicissimus before devoting himself to the design of stage scenery and costumes. In the artist’s theatrical work, his mastery of form, ornamentation, and Orientalism became increasingly evident. He excelled at combining fluid Art Nouveau outlines, with spiky Expressionist passages, and the postures and patterns of the mysterious East.

In his later years, Schnackenberg explored the unconscious, using surreal subject matter and paler colors that plainly portrayed dreams and visions, some imbued with political connotations. His drawings, illustrations, folio prints, and posters are highly sought today for their exceedingly imaginative qualities, enchanting subject matter, and arresting use of color.

SCHNACKENBERG BALLET UND PANTOMIME, a portfolio of 22 color pochoir lithographic prints by Walter Schnackenberg with an introduction by Alexander von Gleichen-Russwurm, printed in an edition of 850, of which 50 examples were numbered and printed on Buttenpapier, commissioned by Kunstanstalt Albert Frisch in Berlin and published by Georg Muller Verlag, Munich, 1920.

Schnackenberg’s contemporary, the celebrated satirical artist Thomas Theodore Heine, described the sophistication, spiritual nature and sensuality of Modern Dance as “praying with your legs.”

In his introduction to Schnackenberg’s portfolio Ballet und Pantomime, Alexander von Gleichen-Russwurm, the godson of King Ludwig and Friedrich Schiller’s heir, writes of its timeliness. He recognizes the portfolio’s uplifting nature in the face of humiliation and defeat in the aftermath of war. He insightfully points out the primal power of Modern Dance and how Schnackenberg expertly and artfully translates his keen sense of movement to the graphic medium. Perhaps most significative is his commentary on Schnackenberg’s creation of a fantasy through the use of classical precedent, exotic cultures and the Carnival tradition. Schnackenberg’s personages assume the roles of wizards, ghosts, flowers, and insects, they are harlequins and an African princess, a Native American shaman, a Vedic dancer and a Waltz dancer; they are man-made items like a powder puff or become the personification of night, itself. A distinctive aspect of the Modern experience is the multiple roles each of us play on a daily basis. While Schnackenberg’s carnivalesque dancers serve as a means of escape through fantasy, they also represent a leveling effect by broadening awareness to augment the possibilities of social existence. Another aspect of modern life which Schnackenberg’s work addresses is the multitude of choices we have and our ability as consumers to make for ourselves something unique out of often-times mass-produced and duplicative items. Schnackenberg’s was not a pessimistic take on modernity, but rather anticipated a gestalt sensibility where one can assemble disparate parts to create an organic structure which functions in a manner greater than the sum of its parts. His dancers are summations of parts, summations of movements: a naturalistically rendered section of torso with deeply shaded regions to accentuate the curve of the rib cage and musculature around the chest and upper arm is balanced by flat patterns of colorful fabric; bare flesh is contrasted by costume; an expressive face pokes out from a fantastical headdress; arms are contorted into mannered poses; feet emerge to complete the amalgamation of pantomimic experience and dynamic movement. Parts become wholes.

Schnackenberg’s prescient understanding of the potentially marginalized and fracturous nature to modern life provides a soothing balm with many possibilities. Indeed, Schnackenberg recognized that dance in his era had moved far beyond the surface of mere visual delight, that dance was the medium - the modern allegory - with which to capture deep feeling and the essence of the modern experience. By designing ballet costumes and illustrating the final outcome of a costumed dancer in full performance mode, Schnackenberg has created his own gestalt of dance which was not only timely for his modern age but resonates powerfully today.