Gustav Klimt Austrian, 1862-1918

1897

Further images

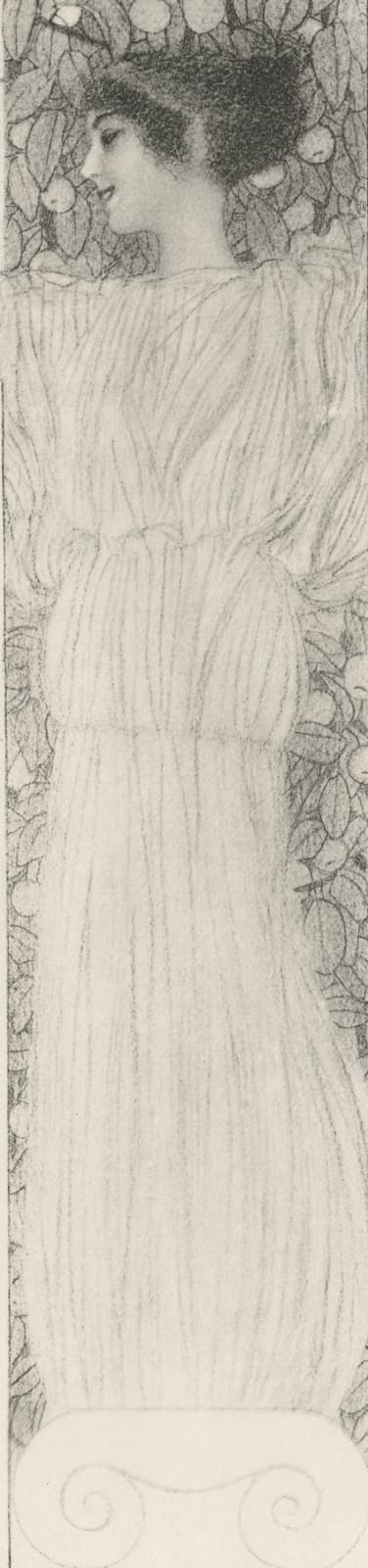

Contributors to Gerlach & Schenk’s publications valued design and innovation in the graphic arts just as much as they examined allegories as subject matter for exploration. Here, Gustav Klimt explores the harmonious relationships of geometry, using the square format for the first time. This 1896 design as an allegory for the month of June exhibits many Jugendstil hallmarks. Fruiting plant motifs and a light, linear style creates a sense of lyricism to what appears to be caryatids who have come to life. These flanking female figures gracefully balance on their ionic bases. The drapery of their flowing tunics softly stirs and undulates with their movement which brings the viewer’s eye optimistically up and center as the caryatids extend their arms out to clasp a branch of ripe pears. Just as there is a harmony in the relationship of the square to the rectangular sections in Klimt’s composition, there is consonance in their gestures. There is concordance in the link between geometry and the use of classical subject matter. However, Klimt was not satisfied with a full reliance upon Classicism; he was interested in creating a modern format for the modern era. Klimt continues along this vein of exploring the possibilities of the graphic medium by closely cropping the profile at center. He renders the image much like a photograph made with the aid of a telescopic lens. Here we see a saturation of color, a more painterly approach to printmaking. The decorative gold tiara finds complimenting echoes in the entire work, at the centers of the daisies and, by degrees, the fair skin against the glowing gold-toned background. For all of the emphasis placed upon the various effects of these formal elements, Klimt pushes further to find an allegory worthy of his time. Klimt gives the viewer an intimate psychological portrait of life ripe with possibilities, in the June of life.

ALLEGORIEN-NEUE FOLGE, 1897, published by Gerlach & Schenk Verlag fur Kunst und Gewerbe, Vienna, was a serial publication that began as Allegorien und Embleme in 1882. A sourcebook of inspiration made for and by young Viennese artists became something of a galvanizer of the modernist movement in Vienna with its new series issued in 1897. Its publisher, Martin Gerlach, plucked young artists and even art students who were exploring the newest techniques in drafting and graphic design to contribute to his publication. This was the beginning of a long-standing relationship. In the forward to the 1897 edition, Gerlach, expounds upon the new approach which consciously shifted away from historicism rooted in the conservative Academy. Instead, the artists were encouraged to explore new subjects and new ways to present them. More unconventional subjects such as: Wine, Love, Song, Music and Dance; Arts and Sciences; the Seasons and their corresponding activities, sports and amusements, breathed fresh, modern life into the allegorical genre. Specific topics that were explored ranged from Electricity and new concepts of Work and Time to Bicycle Sport and the Graphic Arts.

Essentially, the publication served as a portable forum for sharing and disseminating new ideas. Two contributors, a young Gustav Klimt and an even younger Koloman Moser, likely met through their involvement with Allegorien and found themselves to be like-minded artists. As a result, the two allied with other artists and architects in a dramatic and formal break with the established, conservative state-run arts (Kunstlerhausgenessenschaft) to found the Vienna Secession the very next year in 1898. Klimt became the Secession’s first President; while Moser, in 1903, expanded the group from a solely exhibition-based focus to include a workshop by co-founding the Wiener Werkstatte. Gerlach went on to publish some issues of the Secession’s journal called Ver Sacrum as well as postcards designed by its members.

The Viennese art critic, Joseph August, called Gerlach the “Fuhrer der Moderne” (Leader of Modernism). The new 1897 series, featuring its innovative and modern art plates, is an important art historical document as it played a significant role in helping shape the avant-garde art movement in Vienna which exploded onto the scene with the formation of the Vienna Secession in 1898. Individually, the plates are important works; they are noteworthy for their stylistically and thematically modern approach. These plates offer some of the earliest examples of Viennese avant-garde and Secession artists’ published work.

Literature

See "Essential Klimt" by Laura Payne, 2001; pg 49.