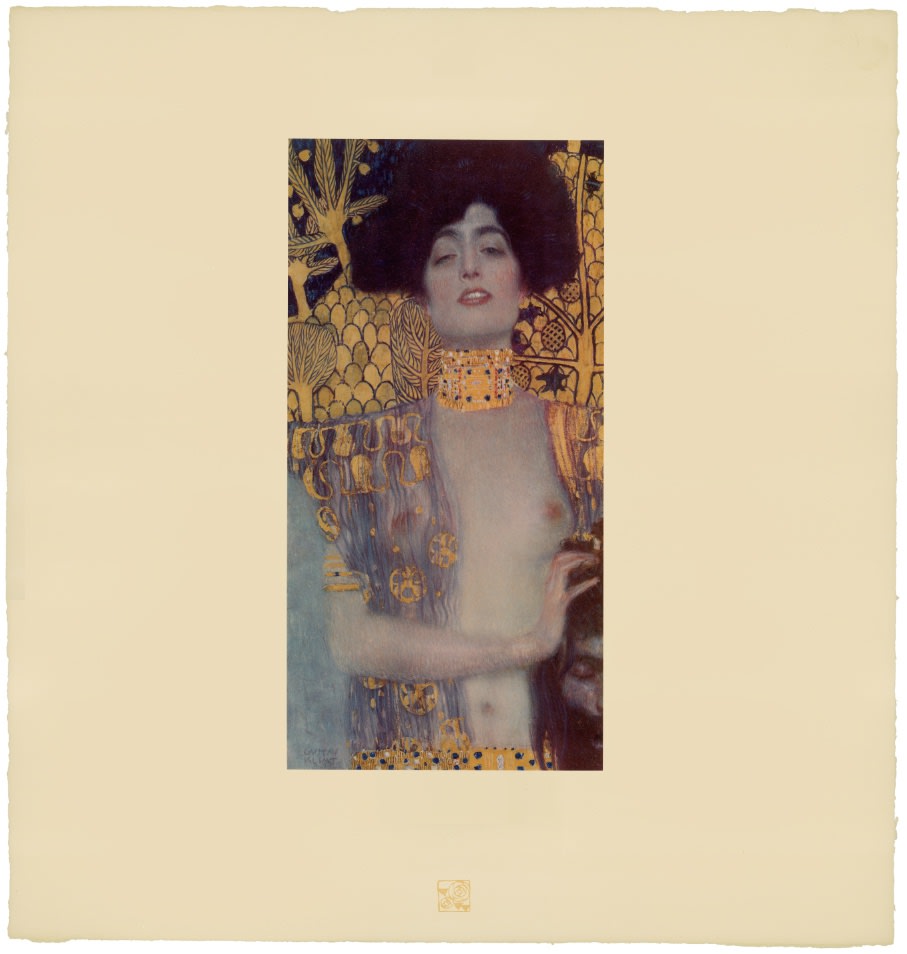

Gustav Klimt Austrian, 1862-1918

1908-1914

Much like his treatment of the Classical personage, Danae, from Greek mythology, Klimt’s depiction of Judith takes an Old Testament character, a heroine who avenges the death of her husband by killing an Assyrian king, and firmly positions her in his present-day Vienna. His multicolored collotype rips the canvas from its gilded frame which directly references the subject with its title: “Judith und Holofernes”. Now in print form, Judith, holding the severed head of a male in murky shadow, is the ultimate Viennese femme fatale. Her likeness is unmistakably similar to a former lover of Klimt’s and famous Viennese soprano, Anna von Mildenburg. Though his allusion to ancient Assyria is apt, Klimt literally lifted the gold patterned background’s design motif from a relief detail from Sennacherib’s Palace displayed in a London museum. His context then is contemporary. In a sensual and sexually powerful tour de force, Klimt’s Judith dares to confront the modern viewer with a physical and psychological portrait of female dominance.

DAS WERK GUSTAV KLIMTS, a portfolio of 50 prints, ten of which are multicolor collotypes on chine colle paper laid down on hand-made heavy cream wove paper with deckled edges; under each of the 50 prints is a gold signet intaglio printed on the cream paper each of which Klimt designed for the publication as unique and relating to its corresponding image; H.O. Miethke, Editor-Publisher; k.k. Hof-und Staatsdruckerei, Printer; printed in a limited edition of 300 numbered plus several presentation copies; Vienna, 1908-1914.

The idea of collaboration in the arts is anything but new; however it has so often been viewed and assessed as somehow devaluing the intrinsic worth of art. It’s as if it was a dirty secret to be hidden away. More so even than the eroticism explored by Klimt, which divided public opinion, the artistic avant-garde began to boldly flaunt artistic collaboration beginning in the 19th century- which gained steam in the first part of the 20th century- to become a driving vehicle of contemporary artistic creation. Viewed in this context, the folios of collotype prints published by H.O. Miethke in Vienna between 1908-1914 known as Das Werk Gustav Klimts, are important art documents worthy of as much consideration for their bold stand they take on established ways of thinking about artistic collaboration as they are for their breathtakingly striking images.

1908 is indeed a watershed moment in the history of art. To coincide with the 60th anniversary of the reign of Emperor Franz Joseph I, Kunstschau opened in Vienna in May of that year. It was there that Klimt delivered the inaugural speech. Speaking about the avant-garde group’s unifying philosophy of Gesamtkunstwerk, or the synthesis of the arts, Klimt shared his belief that the ideal means to bring artists and an audience together was via “work on major art projects.” It was at Kunstschau 1908 that Klimt first exhibited his most iconic painting, The Kiss, as well as The Sunflower, Water Snakes I and II and Danae. It was at Kunstschau 1908 that Das Werk Gustav Klimts was first available for purchase. Thanks to Galerie Miethke’s organization, Kunstschau 1908 was possible. Miethke’s pioneering art house had become Klimt’s exclusive art dealer and main promoter of his modernist vision. Paul Bacher and Carl Moll, a founding member with Klimt of the Vienna Secession, who all broke away during the rift in 1905, took stewardship of the gallery following the fallout with the Secession. Das Werk Gustav Klimts is a prime example of Miethke’s masterful and revolutionary approach to marketing art. Miethke’s innovative marketing strategy played to a penchant for exclusivity. The art gallery and publishing house utilized the press and art critics- such as Austria’s preeminent Art Historian, Hugo Haberfield, who became Director of the gallery in 1912- as a means of gaining publicity as well as maintaining effective public relations. Miethke used the grand exposition format to extend the art gallery’s market reach, cultivating their product’s prestige by stroking the egos of current art patrons while simultaneously creating accessibility for newcomers and others avid collectors to share a relative proximity to other wealthy and respected members of the art collecting community. Essentially, their approach paved the way for what is still the predominant means of marketing.

Between 1908 and 1914, H.O. Miethke published a total of 5 installments of print folios of Klimt’s painted work, each comprising 10 prints. The series was limited in availability to 300 and purchase was arranged through subscription. Each issue was presented unbound in a gold embossed black paper folder. Included in the folio was a Title Page, a Justification page and a Table of Contents page itemizing each of the 10 printed works with details about their corresponding painted works as well as information about each work’s current owner. These folios were not comprehensive of Klimt’s work; but rather, they feature what he believed were his most important paintings from 1898-1913. Only 2 collotypes in each folio were multicolored.

To punctuate the fact that Klimt, himself, was very much an active player in creating these printed works, he created square-shaped signets, unique to each collotype which were intaglio printed in gold ink at the bottom of the cream wove papers to which the chine collie papers were affixed.These signets relate thematically to their corresponding printed images and designate each of those images by their placement in the folio’s Table of Contents page. Functioning much more than simply decorative motifs, these individualized signets provide a distillation of the printed works’s analogous theme. Alice Strobl’s scholarship on this subject confirms Klimt’s involvement throughout the 7-year production process. The Virgin, for example, which dates from c. 1912-1913, was created well after the portfolio was first conceived c. 1908. Its corresponding signet, therefore, could not have been created a priori.

Art Historians, such as Strobl, have shed much light upon the ongoing and collaborative nature of the Das Werk endeavor. Understanding the fragile nature of the collotype printing process also reinforces this project’s distinctive and ground-breaking characteristics. The fragile collotype plates could not be reused. As such, this necessitated the completion of a run on the first go and also dictated the limited production numbers such as the 300 pulled for Klimt’s Das Werk. Printed by hand, the collotypes required deft handling by the printer, k.k..Hof-und Staatsdruckerei. A complicated and lengthy process involving gelatin colloids mixed with dichromates, the creation of 16 color separation thin glass filters to achieve the light-sensitive internegative images which could faithfully capture all of the painting’s tonal gradations and colors, exposure to actinic light, and delicate chine collie papers which allowed for greater color saturation, the printer’s collaborative role in capturing and transmitting Klimt’s nuanced paint strokes is nothing short of remarkable. Ernst Ganglbauer, Director of kaiserlich-konigliche Hof-und Staatsdruckerei (1901-1917) was eager to promote art prints. An innovator, he elevated the Kaiser’s press to international renown by assembling the best of the best in technical and aesthetic advisors. This dream team of free-lance artists developed adaptive uses for the Staatsdruckerei’s existing equipment and, together with the printers there, perfected the multicolor print process for Miethke and Klimt’s Das Werk.

These multicolored collotype prints are perfect examples of what Klimt referred to as “major art projects.” By their very nature, the print medium, these works could bring artists and audience together in a highly accessible way. Each step in the process of their creation required a high level of technical expertise, innovative thinking and true artistic collaboration, Gesamtkunstwerk. The Emperor, himself, was the first to subscribe. His support was firm recognition that Das Werk Gustav Klimts was indeed a masterpiece and product of a dream team enterprise. In the seven-year span that this elite team of talented artists and innovative thinkers produced the complete collection, the Kaiser’s world had radically changed. In just a few years, world war would close with the deaths of Klimt, Miethke, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, marking an end to a fruitful artistic era.